There’s danger lurking in every skincare bottle. Hidden deep beneath glossy marketing claims and polished labels lurk an untold number of comedogenic ingredients that threaten to turn your carefully cared face into acne battleground. Or at least, if you listen to any of numerous comedogenicity experts out there.

As with many other things, commonly accepted ‘beauty blog wisdom’ doesn’t always line up with what the science says. In this post, I’ll show you why you should take comedogenicity ratings with a grain of salt.

Products with comedogenic ingredients aren’t automatically comedogenic

Many beauty bloggers like to post long lists of ingredients ranked by comedogenicity rating. Your duty is to check your skincare products against that list and discard any that contain comedogenic ingredients. This sort of detective work seems so.. scientific, and makes us feel smart.

It’s also utter rubbish.

In 2006 Dr. Draelos and colleagues showed that products with comedogenic ingredients don’t cause acne. Read that again. Products with comedogenic ingredients don’t cause acne.

In the study, they tested ten products with known comedogenic ingredients on 12 people prone to getting back acne. The products were applied on patches on the upper backs of the participants. The patches were changed every 48 to 72 hours, and this went on for four weeks. The researchers counted the number of comedones before and after the study and this was compared to both positive (a highly comedogenic substance) and negative (nothing) controls.

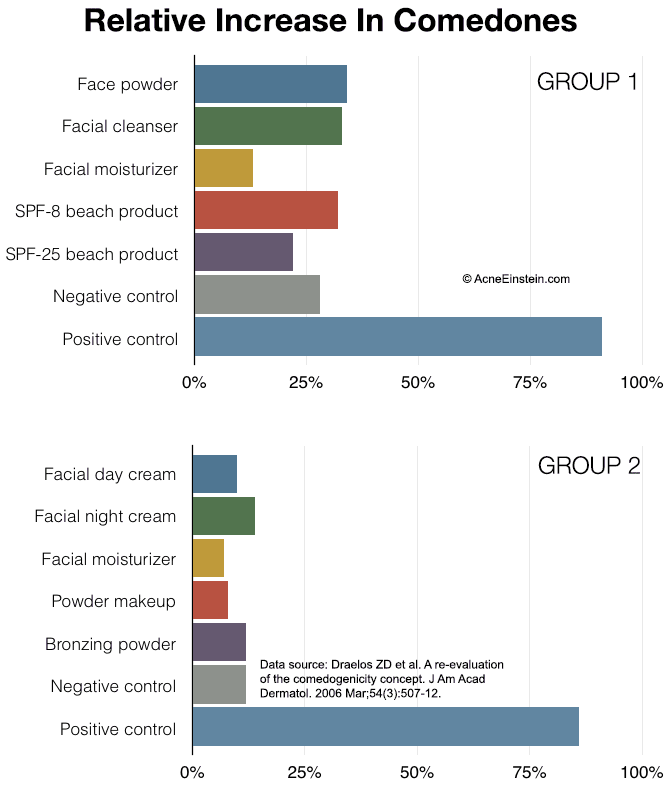

These graphs show the results:

The graphs show the relative increase in the number of comedones before/after the study. The authors note that any results +/- 10% of the negative controls are due to random variation and can be considered as non-comedogenic. The increase you see across the board is due to the fact that the test sites were covered with the test substances and the tapes used to attach them to the skin.

In short, none of the products containing comedogenic ingredients caused acne.

There are limitations to what we can conclude from this study. Most of the ingredients were rated between 1 and 3 on the comedogenicity scale, with only a few that were considered strongly comedogenic.

This apparent disconnect between comedogenicity ratings and real world results leads us to the next point.

Comedogenicity testing doesn’t reflect real life usage

Comedogenicity ratings are appealing because they seem to offer a simple answer to a complex problem. But you should keep in mind that this data hasn’t been generated by observing people using skincare products in everyday life. The data comes from ‘acne models’, both human and animal, and there are severe limitations to what we can conclude from data generated such models.

Even if we set the ethics of animal testing aside, there are serious problems with animal models of acne. Mostly because no other animal gets acne as commonly as humans do, and there are differences in the human and animal skin that probably explains this.

Rabbit ear (REA), the most common acne model, is far more sensitive than human skin and produces scores of false positive results. A 2007 paper examining various acne models concluded that the rabbit ear model is only useful for determining absolute negatives.

Presently, the most commonly used assay is the REA, which possesses a hypersensitive response to acnegenic substances compared to human skin; however, this model is unable to accurately depict the acnegenic potential of chemical compounds, and is therefore only valuable for distinguishing absolute negatives.

Mirshahpanah P. et al. Models in acnegenesis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2007;26(3):195-202. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17687685

Human models, while better than animal models, are still far from perfect. The human models use highly exaggerated conditions to make the tests more sensitive. These include:

- Subject selection. They usually only include people with large pores who are prone to getting pimples.

- Application conditions. The test materials are applied under occlusion, meaning the area is covered after application. This increases absorption and skin penetration.

- Dosage. The test materials are used in high concentrations. This doesn’t take dose response in account. A substance may cause acne at high concentrations but has no effect at concentrations used in skincare products.

2 cases where comedogenicity ratings are useful

This doesn’t mean that we should just throw away all the comedogenicity data. Rather, we should take it with a grain of salt. My view is that comedogenicity data is useful in two cases:

- Determining absolute negatives. Since all the models are more sensitive than real life usage conditions, a substance with comedogenicity rating of 0 to 1 should be safe.

- Determining the worst offenders. Substances that rank high on the comedogenicity scale should be treated as potential suspects.

There’s so much uncertainty in the comedogenicity data that it’s not very useful for anything that falls between those two extremes.

Comedogenicity rule of thumb

I condensed everything that we’ve discussed earlier into a simple rule of thumb.

Be wary of products with strongly comedogenic ingredients high up on the ingredients list. Otherwise, forget about it.

Some people may challenge me and say ‘the rule is dangerous because my skin always reacts to even mildly comedogenic ingredients.’ That may be so, and I don’t doubt some people are like that. My point is that comedogenicity ratings are not reliable enough to make generalized recommendations. They may be helpful for someone, but then again, even a broken clock is correct twice a day.

And of course, avoid any products/ingredients you know your skin reacts badly to – regardless of their comedogenicity rating.

Conclusion

To me comedogenicity ratings are a bit like astrology – just because someone made elaborate charts and systems, doesn’t mean it’s correct. The scientific-looking ratings hide severe limitations.

The models used to generate the data are far more sensitive than real world skincare product usage, and they produce scores of false positive ratings. As such, the data isn’t very useful in guiding everyday skincare choices.

The best we can say is to avoid products with highly comedogenic ingredients high up on the ingredients list and ignore the rest.