The simplest and most effective ways to fix bacterial overgrowth is to starve them. Most problems stem from carbohydrate fermentation (especially if you struggle with gas and bloating), so we start by limiting fermentable carbohydrates. The keyword here is fermentable, and we’ll get to that in a minute.

Reducing food supply starves the bacteria in the small intestines. It also favors the healthy bacteria over harmful bacteria in the large intestines. The healthy bacteria have evolved and specialized to thrive in the human digestive track. Reducing overall food supply means the healthy bacteria can outcompete the harmful bacteria and thus also improve the bacterial balance in the large intestine.

Fermentable carbohydrates

We can divide carbohydrates into two groups: simple (sugars, etc.) and complex (starches, fiber, etc.). This classification is based on how quickly they are digested and absorbed. Simple sugars are digested and absorbed rapidly, some even while they are in the mouth. Whereas complex carbohydrates need to be chopped down into simple sugars, which are then absorbed.

The conventional wisdom says that complex carbohydrates are healthier, which is largely true. But for people with gut problems the opposite is true.

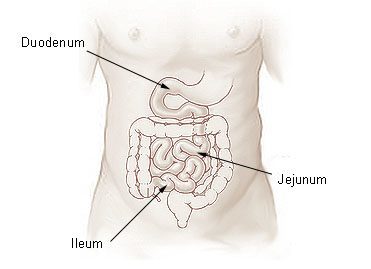

The small intestine is divided into three parts:

Image from Wikimedia commons.

- Duodenum

- Jejunum

- Ileum

Wikipedia on carbohydrate digestions:

In the typical Western diet, digestion and absorption of carbohydrates is fast and takes place usually in the upper small intestine (duodenum). However, when the diet contains carbohydrates not easily digestible, digestion and absorption take place mainly in the ileal portion of the intestine.

When you eat simple carbohydrates, the vast majority of them gets absorbed in the upper part of the small intestines (duodenum), whereas complex carbohydrates require more enzymatic digestion and are absorbed towards the end of jejunum and in the ileum.

The upper parts of the small intestine have orders of magnitude fewer bacteria than the lower parts. Here are rough estimates of bacterial densities in the intestines (source: Microbe Wiki)

- Duodenum: 10^1 to 10^3 CFU/mL (CFU: colony forming units)

- Jejunum and ileum: 10^4 to 10^7 CFU/mL

- Large intestine: 10^11 to 10^12 CFU/mL

The important point is that the upper part of the small intestine is sterile compared to the lower parts and the large intestine. So carbohydrates absorbed in the upper part are not available for bacteria to ferment and thus are far less likely to cause gut problems (aside from severe cases of SIBO that involve overgrowth in the duodenum and the stomach).

Determining carbohydrate fermentability

Most of what follows is adapted from Dr. Norm Robillard’s book Fast Tract Digestion, which I highly recommend you to read. Dr. Robillard says that the carbohydrate types most likely to cause fermentation are:

- Lactose (in dairy products)

- Fructose

- Resistant starch

- Fiber

- Sugar alcohols (such as xylitol, sorbitol, mannitol, isomalt)

That knowledge alone doesn’t help you much as it’s difficult to know how much of the above any given food contains.

However, Dr. Robillard developed a formula for estimating carbohydrate fermentability of a given food. He calls this measure fermentation potential (FP). Math alert! You can calculate FP for a given food with the following formula:

FP = (100 – GI) / 100 x NC + DF + SA

In which:

- GI means glycemic index

- NC means net carbs (total carbohydrates minus fiber and sugar alcohols)

- DF means dietary fiber

- SA means sugar alcohols (Sorbitol, erythritol, mannitol, xylitol, isomalt – typically used as low-calorie sweeteners and mostly found in processed foods, amount usually listed on the nutrition facts label)

It’s simpler than it looks. Let’s run through this.

- Start by finding the glycemic index for the food. The simplest way is to just type the food name and GI into Google.

- Deduct the GI from 100 and divide the result with 100. This part is kind like the GI in reverse. The GI estimates the amount of quickly absorbed carbohydrates in a given food. Quickly absorbed carbohydrates aren’t fermented, and thus, we aren’t interested in them. The first part of the formula [(100 – GI) / 100] simply estimates the amount of slowly absorbed carbohydrates. Let’s take a few examples. Carrot has GI of 71. Applying our formula to that we’ll get 0.29 [(100 – 71) / 100 ] or 29%. White bread has GI of 95; so we’ll get 0.05, or 5%. If GI is 100 or more, this means all the digestible carbohydrates are quickly absorbed and you don’t have to worry about them.

- Figure out net carbs. For this, you need to know the portion you are eating. Net carbs is total carbohydrates minus fiber and sugar alcohols. You’ll find this data either on the label of searching Google for food name and nutrition data. If sugar alcohols aren’t listed, just deduct the amount of fiber from total carbohydrates.

- Multiply the figure from step #2 with net carbs from step #3.

- Add the amount of fiber and sugar alcohols (if known)

The result of this formula is the amount of fermentable carbohydrates (in grams).

Let’s do a few examples. Most of this data is available from https://nutritiondata.self.com

Medium carrot (61 grams)

- GI: 71

- Total carbs: 6g

- Fiber: 3g

- Sugar alcohols: 0g

FP = (100 – 71) / 100 x 3g + 3g = 5.13g

Muesli with dried fruits and nuts (1 cup, 85g)

- GI: 69

- Total carbs: 66g

- Fiber: 6g

- Sugar alcohols: 0g

FP = (100 – 69) / 100 x 60g + 6g = 24.6g

So a bowl of muesli has roughly 6 times more fermentable carbohydrates than a carrot does. As we discussed earlier, 30g or fermentable carbohydrates produces 10 liters of intestinal gas. So that bowl of muesli can produce over 8 liters of gas.

Corn flakes

Let’s see what happens if you would eat corn flakes instead. We need almost 3 cups of corn flakes to get the same amount of calories than from a bowl of muesli. Here are the figures for corn flakes:

- GI: 92

- Total carbs: 67g

- Fiber: 3g

- Sugar alcohols: 0g

FP: 8.4g

I know it’s inconvenient to calculate FP for all of your foods. That’s one reason I recommend getting Dr. Robillard’s book. At the appendix, he has tables that list FP for hundreds of different foods.

The upside is that you only have to do this for 2 to 3 weeks. You can also get a rough estimate just by looking at GI. Most foods with high GI have little to no fiber (except for some fruits).

Fermentation potential guidelines

Dr. Robillard gives the following guidelines:

For a single meal:

- Low: FP 7 grams or less

- Moderate: FP 8 to 15 grams

- High: FP 16 grams or more

For daily total:

- Low: FP 20 – 30 grams

- Moderate: FP 31 – 45 grams

- High: FP over 45 grams

For this initial phase, I recommend you limit fermentable carbohydrates to 30 to 35 grams a day.

Dietary guidelines

If you don’t feel like calculating FP for your foods, you can follow these guidelines instead. Obviously, this doesn’t give you as good results, but this might be sufficient.

These guidelines apply to people who struggle with bloating, gas, indigestions, and other such problems that stem from carbohydrate fermentation. In some cases, gut issues arise from fat malabsorption. In such cases, a different type of diet is required.

- Limit your overall carbohydrate intake. Eating drastically fewer carbohydrates is probably the simplest way to reduce carbohydrate fermentation. You may consider low-carb diet during this initial treatment phase.

- Limit fruits to 1 to 2 servings per day. Watermelon, cantaloupe, pineapple, peaches, apricots, and strawberries all have low FP (6 grams or less per serving). Bananas, dried fruits, and figs have FP of 15 grams or more. Other fruits fall in the middle.

- Avoid pasta and other grain-based foods, and especially whole grain varieties that have lower GI and more fiber.

- Instead of grains, choose starchy vegetables (potatoes, rice). Go for white potatoes over yams and sweet potatoes. Boiled white potatoes have GI over 80; some varieties are above 100. In contrast, yams and sweet potatoes score between 55 and 70. Similarly, choose white rice over brown. Go for Jasmine or other Asian rice varieties, all of which have GI over 90 and little to no fiber. Basmati rice has much lower GI and more fiber, and thus more potential for fermentation.

- Cook starchy vegetables thoroughly and avoid eating leftover rice or potatoes the next day. The reason is that cooking and cooling forms resistant starches. Humans can’t digest resistant starches and rely on bacteria to ferment them. However, resistant starches are very good for the gut and can be eaten at later stages.

- Include reasonable amounts of non-starchy vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, cabbage, lettuce, etc.) to keep your bowels moving and to ensure you get enough nutrients. Most non-starchy vegetables have negligible amounts of carbohydrates. Eaten in moderate quantities, the fiber shouldn’t be a problem. Just be careful with broccoli, cauliflower and other ‘rough’ vegetables.

- Cook hardy vegetables (carrots, broccoli, etc.) to reduce the amount of fermentable fiber.

- Avoid most dairy products (high in lactose). You can have as much butter as you want as it doesn’t have lactose or dairy proteins. Small amounts of yogurt and hard cheeses are also OK. Fermentation process gets rid of a good portion of the lactose. According to Dr. Robillard’s calculations, a cup of plain yogurt has FP 4 grams as compared to 8 grams for a cup of milk. Do make sure that it’s plain yogurt. Many manufacturers add fruits and fructose which quickly bumps up the FP. A cup of low-fat yogurt sweetened with fruits and sugar has FP 24 grams.

Keep in mind

These calculations are by necessity simplistic. They give you an idea of the fermentation potential of individual foods. But they leave out some important points.

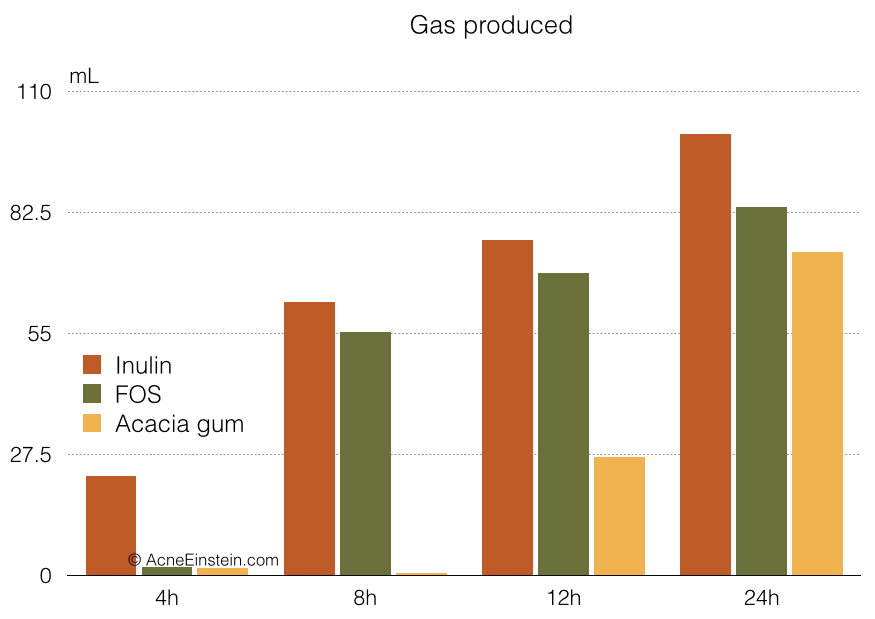

Some carbohydrates are fermented much faster than others. A 2014 study nicely illustrates this. The researchers cultivated common human gut bacteria on a petri dishes and fed them different fibers. They then measured the amount of gas produced at various time points. This graph shows the total amount of gas produced at each time point.

Source: Koecher, K. J. et al. Estimation and interpretation of fermentation in the gut: coupling results from a 24 h batch in vitro system with fecal measurements from a human intervention feeding study using fructo-oligosaccharides, inulin, gum acacia, and pea fiber. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62,1332–7 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24446899

Inulin and FOS are different types of FODMAPs, and Acacia gum is a type of gut-friendly fiber we’ll talk more in the next section.

Inulin yielded 23% of total gas within the first 4 hours and 63% within the first 8 hours. FOS was slower to get started but also released 65% of total gas within the first 8 hours. In contrast, Acacia gum released almost no gas within the first 8 hours.

It takes 6 to 8 hours for food to pass through the stomach and the small intestine. So, for people with SIBO, a significant portion of the gas produced in the first 8 hours ends up the in the small intestine.

The point is that fermentation potential calculations produce good estimates and guidelines. However, you still need to keep an eye out for foods that you might react badly to. Foods high in FODMAPs are potentially risky and should be kept an eye out for.

How long to see results and stay on the diet

Before we finish, let’s go over how long you should remain on this ‘gut bug diet’. The short answer is as long as it takes to get rid of most of your digestive symptoms.

Bacteria have short lifespans, and it shouldn’t take too long to starve them out. Most people will notice significant improvements within the first 2 to 3 days.

That being said, I recommend staying on strictly limiting fermentable carbohydrates for at least 2 to 3 weeks. This is because it takes some time for the small intestine to heal and you want to make sure it’s prepared when you start adding fermentable carbohydrates back to your diet.

On the flip side, I also don’t recommend staying on very low fermentable carbohydrate diet for too long. Bacterial fermentation in the large intestine is very healthy. It provides nutrients we couldn’t otherwise get and prevents harmful bacteria from colonizing the intestines.

The elemental diet

The elemental diet is an extreme version of the diet covered here. I don’t recommend you start with it, but it can be an option for those who don’t see results from limiting fermentable carbohydrates. See the elemental diet page for more in this extreme option.